POLAROIDS

POLAROIDS

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_images_carousel images=”2066,2069,2067,2068″ img_size=”full” onclick=”link_no” hide_pagination_control=”yes” wrap=”yes” el_class=”carousel-size-vert”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]BOOK

Carlo Mollino: Polaroids

by Damiani (second edition)

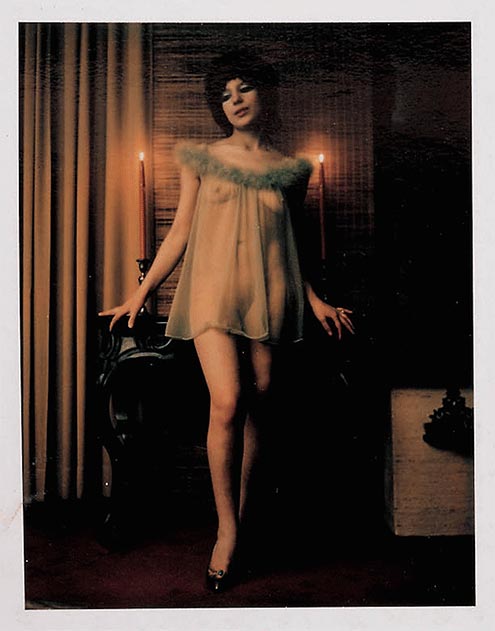

Carlo Mollino (1905-1973), was a stunt-pilot, race-car driver, writer, celebrated architect, designer and a playboy bachelor with two apartments, a studio and a villa, all in the northern Italian city of Turin. In this short sketch of biography we can perhaps see elements of the sort of dandified machismo that leads a man to demolish and reconstruct the interior of one’s villa, rename it The Warriors House of Rest, and use it to serve his secret passion for erotic photography.

The book is a collection of these photographs, selected from the roughly 1200 surviving Polaroids, never exhibited during his life, which were found following his death in 1973. The images are best described by adjectives closely associated with the presence of money: rich, sumptuous, lavish. They are all eroticized images of women, but the subject is not sex. It’s clear that more so than the human body, Mollino was attracted to the aesthetic abstraction of beauty as a lifestyle. The photographs have been composed, staged and directed with the desire to conquer nature with artifice. The women in the photographs recede into the crimson carpeting, the blue velvet curtains, wigs, furs, champagne, animal skins, leather, lingerie, the Eero Saarinen chair and the 1960’s haute-couture – the handpicked accoutrements of Mollino’s private paradise. Even nude, Mollino’s subjects retain the mark of his direction through angle and pose. The majority of the shots are taken from the same angle, with the female subject raised on the stage-like platform Mollino, architect of Turin’s opera house the Teatro Regio, had INSTALLED in the theatre-like main room of his villa.

in the theatre-like main room of his villa.

As an architect and designer, Mollino spent his life crafting forms to accommodate the human body, but in his photography there is the apparent desire to reverse the order of supremacy and make the human form an element of design. There are strong echoes between the shapes of his human figures and those in his furniture. The smooth curves of a glass tabletop recalls the female torso. A woman lying with her legs curled back so as to nearly touch her back recalls the folds and undulations of the molded wood on his furniture.

Many images feature sumptuous, thick backgrounds of black velvet broken only by a feminine form painted warm, blonde light with a softness unique to the Polaroid. Other images show women amongst blue and white tile floors and icy, white lace, against which their SKIN tones take on an unhealthily fair, almost spectral quality. A majority of the photographs, however, are shot in front of a foldable, hanging matt made of woven reeds. The matt infuses the photographs with a golden, flax-colored warmth, but is evocative of no place other than the studio. The repetition of the hanging backdrop coupled with the interchangeable, costumed and anonymous models before it quickly works to establish an aura of claustrophobia and uncanny misrecognition which give the seemingly appealing scenes a sinister aura.

tones take on an unhealthily fair, almost spectral quality. A majority of the photographs, however, are shot in front of a foldable, hanging matt made of woven reeds. The matt infuses the photographs with a golden, flax-colored warmth, but is evocative of no place other than the studio. The repetition of the hanging backdrop coupled with the interchangeable, costumed and anonymous models before it quickly works to establish an aura of claustrophobia and uncanny misrecognition which give the seemingly appealing scenes a sinister aura.

Whereas Playboy would print foldouts of inviting, airbrushed women with names and backstories calculated to appeal to the market-audience, Mollino’s work consists of small, unretouched and anonymous pieces of private collection. The repetitive, secretive way Mollino went about creating his collection has more in common with the practice of an outsider artist than that of a pin-up photographer. As the women recede into the collection of the other anonymous models the architect comes forward and it becomes apparent that Mollino’s Polaroids are portraits not of their subjects but of the desires of the photographer. Mollino never married and it’s unclear if his life had a love; what is clear is that he felt passionately about, perhaps loved, things.

In A Rebours, J.K. Huysman’s definitive decadent novel, the wealthy, leisured antihero, Jean Des Essientes, sickened by society, syphilis and humanity at large retreats into his villa where he attempts to ascend to a higher spiritual plateau through the aesthetic refinement of his villa’s interior. His desire, which proves untenable, is to have art replace life. There is much of desire in Mollino’s photography. Photographs remain constant in a way that humans do not, and you can keep them in an envelope. It is easy to trap beauty for a moment on paper, but impossible to sustain such an image throughout a life.

The eros in Mollino’s work assumes a melancholy, poisonous aspect with the understanding of the circumstances of its production: part of an aging bachelor’s desire to perfect the decoration of his house. There is something of satyriasis, or Don Juanism, the male equivalent of nymphomania, in Mollino’s work, as if they were undertaken compulsively, and perhaps without joy, as part of a doomed project to reach an unattainable ideal: the tragic desire to keep thousands of women in an empty house.

(courtesy of ASX, Nov. 2014)[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Recent Comments