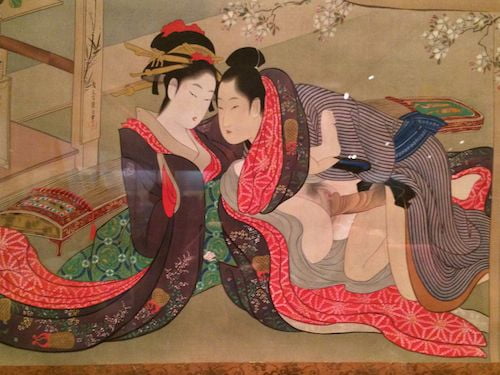

SEX & PLEASURE IN JAPANESE ART

SEX & PLEASURE IN JAPANESE ART

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_single_image image=”3453″ img_size=”full”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][vc_column_text]Shunga, Sex & Pleasure in Japanese Art

British Museum

photos: nathalie hambro

“Pillow pictures (shunga) are the most important items for a bride’s trousseau. For men as well these are essentials. If we ask why this is the case, the answer is that sex is essential to give pleasure to one’s heart. This is the reason it is found in the armour chests of samourai as well”

Yoshida Hanbei, Genji on iro-asobi, 1681

Shunga were mostly produced within the popular school known as ‘pictures of the floating world’ (ukiyo-e), by celebrated artists such as Hishikawa Moronobu (died 1694), Kitagawa Utamaro (died 1806) and Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849). Earlier, medieval narrative art in Japan had already mixed themes of sex and humour. Luxurious shunga paintings were also produced for ruling class patrons by traditional artists such as members of the Kano school, sometimes influenced by Chinese examples. This was very different from the situation in contemporary Europe, where religious bans and prevailing morality enforced an absolute division between ‘art’ and ‘pornography’.

It is true that official life in this period was governed by strict Confucian laws, but private life was less controlled. Banned after 1722, but rarely suppressed in practice, shunga publications flourished on the boundaries between these two worlds, even critiquing officialdom on occasion. Paintings were never the object of censorship, and national networks of commercial lending-libraries, the main means of distribution for shunga books, were not regulated.

Early modern Japan was certainly not a sex-paradise. Confucian ethics that focused on duty and restraint were promoted in education for all classes, and laws on adultery, were severe. There were also many class and gender inequalities, and a large and exploitative commercial sex industry (the ‘pleasure quarters’). However, the values promoted in shunga are generally positive towards sexual pleasure for all participants: in one memorable colour print from the series Erotic Illustrations for the Twelve Months of c. 1788 by Katsukawa Shuncho (worked 1780s-1790s), for instance, a husband and wife enjoy lovemaking at a window in mid-summer, to the cry of a cuckoo. Women’s sexuality was readily acknowledged and male-male sex recognised in particular social contexts. Although men were the main producers and consumers, it is clear that women also were an important audience; the custom of presenting shunga to women in a marriage trousseau seems to have been common, and some works seem to have been created more for women than for men. During the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, shunga was all but removed from popular and scholarly memory in Japan and became taboo. Ironically, it was just at this time that shunga was being discovered and enthusiastically collected by European and US artists such as Lautrec, Beardsley, Sargent and Picasso. The British Museum acquired its first shunga prints as part of the George Witt Collection in 1865 and now has one of the best collections outside of Japan.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][vc_single_image image=”3454″ img_size=”full”][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][vc_single_image image=”3455″ img_size=”full”][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][vc_single_image image=”3456″ img_size=”full”][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][vc_single_image image=”3457″ img_size=”full”][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][vc_single_image image=”3458″ img_size=”full”][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][vc_single_image image=”3459″ img_size=”full”][vc_empty_space height=”50px”][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text css_animation=”none” el_class=”with-link”]![]() back to ART DIARY[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

back to ART DIARY[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Comments are closed.